SizeCoding is an attempt to pack things into as little code or compiled code as possible. In this way, the method also follows the human endeavour to pack ‘a lot into a little’ and still keep it controllable. So a small model has great significance. But science also sings its song of simple formulas with a lot of power. Today, the whole thing is also a question of sustainability – for example in the discussion about big data AI and learning.

In other words, it’s about power and control. The fewer characters are used, the more magical/powerful the ‘code’ is. Here, of course, homage is also paid to the machine and the disembodied ‘self’. Hence, of course, the connection to the demoscene and its emergence as intro crack demos.

Of course, size coding used to be a must in game design. How much ‘game’ can you fit into an 8K module, etc.? Today, size coding is rather obsolete – because readability and therefore maintainability are usually neglected.

Sizecoding-Method

But size coding is also a cognitive and therefore scientific method.

Why? Because SizeCoding iteratively poses questions that need to be answered in the search for the smallest possible programme for a game/software/task. And this automatically leads – with sweat – to insights about the individual games.

You arrive at the smallest possible programme/game by asking the following questions:

- Question of game mechanics: Core mechanics?

What is the game, what is the core? What is the minimum? What must be implemented as the minimum? In other words: What makes game X a game X? - What implementation?

How is the game implemented? The implementation of a game can be different. So there are different approaches to realising a game. - Smallest possible implementation?

The next question is, how big are the implementations? What can be saved and what can’t? Do you have to go further with 2 and solve the whole thing completely differently? - When were certain game mechanics even realisable? (Historical)

All 4 questions are interwoven and therefore cannot simply be separated. And the advantage of a concept is usually also its disadvantage.

Approaches

There are at least 2 approaches for SizeCoding:

In the top-down approach, there is an existing problem A. This would like to be solved in as few characters as possible.

In the second approach, bottom-up, the aim is to do as much as possible with the possibilities.

The motivational design is different in both approaches at first. However, it can be seen that motivational design also occurs in the first top-down approach, especially when there are still characters left or characters could be saved.

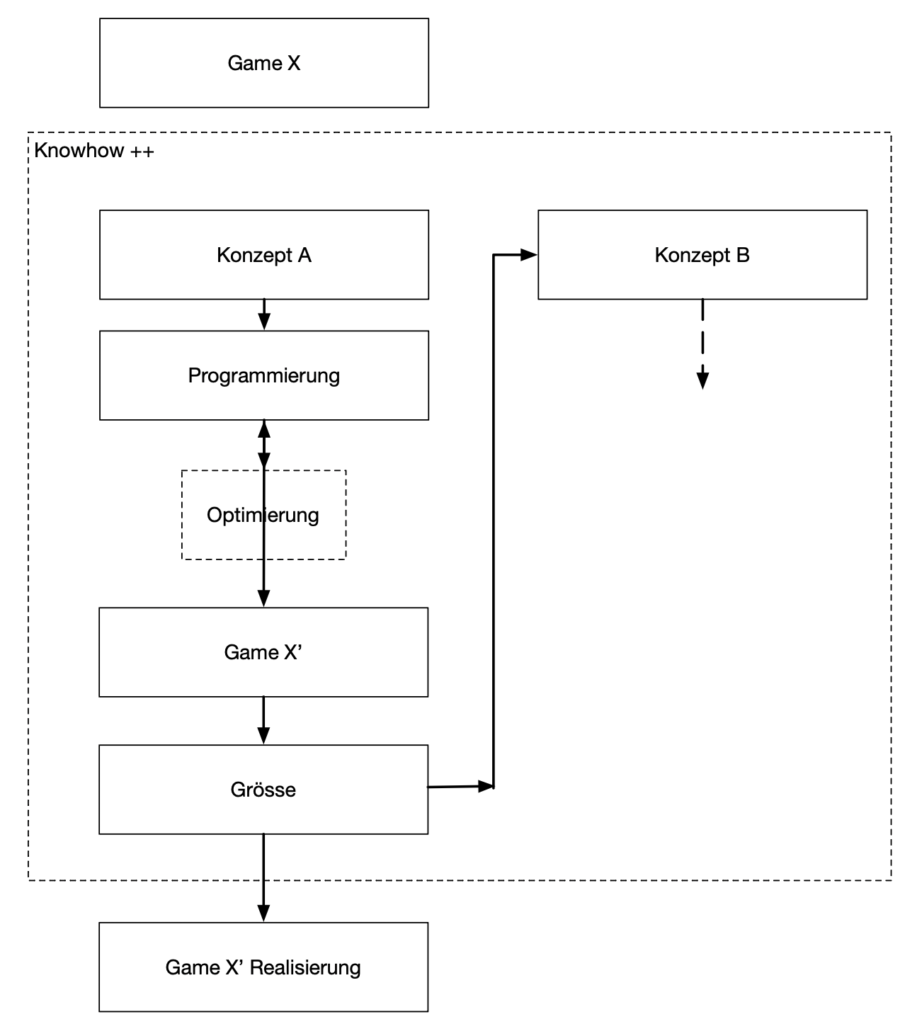

Coders* often switch from A to B if A did not work out and then use their knowledge in the opposite direction. Or an oscillating method is used – probably often observable in the demoscene: TopDown and then BottomUp again and then TopDown again etc.

The phenomenon of the top-down approach will be examined in more detail here, because this is where the most (?) can be learnt about existing games. Of course, the bottom-up approach also yields insights. But this is more of an XYZ approach.

Approach: Top-Down – Target game available

If there is something that needs to be achieved, such as recreating a Tetris or a Breakout. Then an attempt is usually made to programme the game using the classic/standard approach.

The first approach is therefore usually the approach in the genesis of the game, i.e. the standard implementation, so to speak. After implementation, an attempt is then made to make the code leaner. To integrate things: Such as using loops multiple times, using fewer variables, etc.

If this implementation fails despite this – because the whole thing cannot be implemented and the optimisation is hopeless: the code is about 4 times the possible amount (something like a nanogame for 256 bytes) then there is nothing else to do but to find a new concept. And to try again.

This can result in quite abstruse implementations that are really smaller and now utilise the peculiarities of environments, for example.

Gains in knowledge

The longer sizecoding is used as a method of realisation, the clearer the minimal concept of a game becomes – precisely because more and more has to be removed until only the core concept is playable. And something is always taken away that ‘destroys’ the game and turns it into something else. So it’s a kind of bonsai game (even if the comparison is massively flawed). Perhaps one could even speak of the idea of the game.

The applied discussion also quickly shifts the focus to the technical conditionality of game concepts. What is minimally necessary, how much code is needed to realise this or that. If X is removed, what is missing – also in the motivational design. Sizecoding therefore also forces us to look at games differently: What is it actually about?

Throughout the entire process of this applied research, expertise is of course also generated directly by the applied researcher*, which is then in turn incorporated into classic game development processes.

Sizecoding is often organised via competitions. This results in many different approaches to how games can be programmed and realised. This also creates a kind of world of variation of different approaches.

Zur Frage der Kreativität in diesem Prozess more here >

Case: Breakout

Here the discussion is applied to the example of a breakout in a FantasyConsole & Co >