The dawn of the German Football Management Games

Starbyte Super Soccer is one of those early football management games (genre: strategy). The name had to be chosen that way because there were other products with the same name Super Soccer, for example from Nintendo. And Starbyte itself already had another soccer strategy game on offer with Soccer Manager Plus (1989). Two years later, the new soccer manager game focused on the German Bundesliga and tried to be as accurate as possible.

The Atari ST version of Starbyte Super Soccer was released for Christmas 1991. The PC version as well. The Amiga version programmed by Swiss René Straub a few days later.

The game is clearly a German game. Starbyte had taken it out of the public domain and ported it first from Atari ST to Amiga. Credit for designing it gets Dirk Weigand. As a teenager he had worked on the predecessor Kicker and released his soccer manager in 1990/91 under a label that he called PolarSoftware. Kicker was one of the first German-language soccer management games. Weigand, who lives in Troisdorf (north of Bonn), was inspired by the 1984 Footballmanager on the ZX Spectrum and had developed his own football manager from 1987 on. His new football game was supposed to stand out from other comparable games with several new features.

Dirk Weigand owned an Atari 600XL and soon reached the limits of what was possible with it, as the computer only had 16 kilobytes of memory. He owes the progress in development to his „rich godparents from Switzerland“, who enabled him to buy an Atari ST for his confirmation. The game was programmed with GFA-Basic 2.0. Basic also made it possible to compile the software to an independent program. Brother Frank and stepfather Bernd helped at least conceptually and with constant testing. 16-color sprites were contributed by Oliver Merklinghaus. And Dirk Weigand won the listing of the month in Atari Magazine for the month of January 1989.

Start screen of Dirk Weigand’s soccer manager KICKER, which was released as shareware in 1990.

Completed in 1990, Kicker was first distributed and played only among acquaintances and friends. In the German computer magazine Aktueller Software Markt ASM 8+9/90, the game was then presented in a new column, and Weigand was contacted by the company Micropartner, which wanted to distribute the game. Since the company could not port the program, the deal fell through, and Weigand saw only the way of self-publication. The game could then be ordered from him as shareware program for 30 DM. Weigand remembers that he had about 100 orders in total. His Kicker was also included on some shareware CDs.

At the beginning of 1991 the German publisher Starbyte Software from Bochum contacted Dirk Weigand and made a deal with him. Besides the Atari ST version, the game should be ported to Amiga, PC and C64. At the end of 1991 the Atari ST, PC and Amiga versions were released. The C64 version was released one year later. Starbyte renamed the soccer management game with the new title Starbyte Super Soccer, which Weigand did not like. But keeping the title KICKER seemed not possible considering the biggest German football magazine at the time that was called KICKER. The new versions of the soccer management game were complemented with new graphics for the program start, music, and stadium sounds. The rest remained the same.

And this is the Swiss connection:The Amiga version of Starbyte Super Soccer was programmed by Swiss René Straub, who had already worked on other ports for Starbyte Software.

Start screen of Starbyte Super Soccer

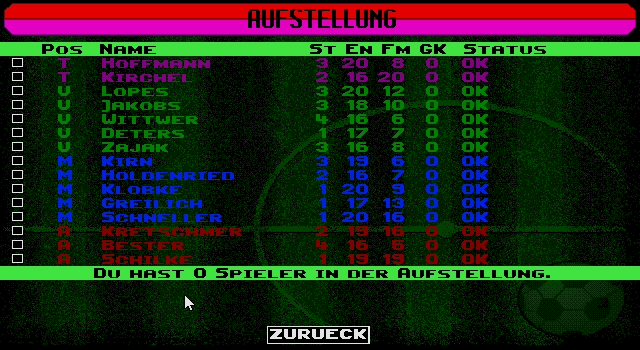

The formation of the own team and the match tactics for each game are the heart of the soccer manager game. In Starbyte Super Soccer as in other similar games, the matches themselves are not visually shown or performed. Each time after finishing formation and tactics, the player gets a result and a report on the match.

In Starbyte Super Soccer, the player is allowed to take on the role of both manager and coach. And up to six players can take over their own teams at the same time; it just gets a little crowded in front of the computer. Weigand was at least proud of the review by popular game editor Heinrich Lenhardt, who ranked the game among the 100 best games in the 1991 Powerplay special issue and gave it an excellent 80% rating. But success was a long time coming, as two other football managers appeared almost simultaneously namely Bundesliga Manager Professional (1991) and Anstoss – der Fussballmanager (1993). And then, of course, there was the bankruptcy of the publisher Starbyte, so that the payments that were agreed upon in the contract, failed to materialize in 1992. From 1993 on, the game was then distributed by the re-founded company Starbyte Software. However, Weigand did not get much money. He had already written off the game and preferred to concentrate on his studies.

Not a good game for the Würzburger Kickers … – lineups, consequences and results are shown on the background of the field, followed by the table.

After more than 30 years Dirk Weigand was motivated again by an interview of Denis Roters about video game history. In 2021 he sat down again and went through the recovered source code of the old game KICKER and corrected an important bug in GFA Basic 2.0 which had hindered the start of the game in the emulator. So today, you can find a newly worked out disk image for Atari ST as well as emulations for various contemporary platforms on a very well documented website by Frank and Dirk Weigand.

(Beat Suter, CH-Ludens, 07.08.2023 / 17.08.2023)

Sources:

Denis Roters. Wie Starbyte Super Soccer in mein Leben kam. In: Videospielgeschichten, 25.04.2020.

Website zur Entwicklung von Kicker (Dirk Weigand), erstellt von Frank Weigand 2021

Listing des Monats (Atari Magazin, Januar 1989)

https://kicker.weigand.xyz/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Atari-Magazin-89-01_ListingMonat.pdf

ASM 8+9/90, Microwelle, Vorstellung von Kicker, S. 156

https://kicker.weigand.xyz/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Kicker_ASM_8_9_90.jpg

Die 100 besten Spiele: Starbyte Super Soccer. In: Powerplay, Sonderheft 3, 1991, S. 94

https://kicker.weigand.xyz/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Power-Play-Sonderheft-1991-03_SSS-Kopie.png

Interview KICKER mit Denis und Dirk (2.24 Stunden) auf Vimeo